Chapter 7 Tagging data exploration

Since 1972 there have been approximately 400 000 sablefish tagged in Alaska waters, of which over 38 500 have been recovered. Although there is extensive and long term tagging data, this information is not currently directly included in the stock assessment (D. Goethel et al. 2021).

Historical publications investigating movement of Alaskan sablefish include Heifetz and Fujioka (1991), Hanselman et al. (2015)

Data grooming

| rule | events | events_removed | relative_events |

|---|---|---|---|

| Init | 36159 | 0 | 0.00 |

| Duplicated recovery id | 36104 | 1085 | -2.92 |

| negative time-at-liberty recovery id | 35884 | 220 | -0.61 |

| NA lat and long | 35884 | 0 | 0.00 |

| Tag type: AB, BK, JU, SA, SB | 30986 | 4898 | -13.65 |

| Area: BS, AI, EGOA, WGOA, CGOA | 22535 | 8451 | -27.27 |

| Gear recovery: 901, 902 | 19214 | 3321 | -14.74 |

| Exclude survey recoveries | 16805 | 2409 | -12.54 |

| Release code: 623, 901, 902, 915 | 13267 | 3538 | -21.05 |

| Release depth > 150 | 10850 | 2417 | -18.22 |

| rule | events | events_removed | relative_events |

|---|---|---|---|

| Init | 395146 | 0 | 0.00 |

| Duplicated recovery id | 390768 | 4378 | -1.11 |

| NA lat and long | 390767 | 1 | 0.00 |

| Tag type: AB, BK, JU, SA, SB | 337603 | 53164 | -13.61 |

| Area: BS, AI, EGOA, WGOA, CGOA | 276427 | 61176 | -18.12 |

| Release code: 623, 901, 902, 915 | 241525 | 34902 | -12.63 |

| Release depth > 150 | 202563 | 38962 | -16.13 |

Exploratory analysis of the tag data

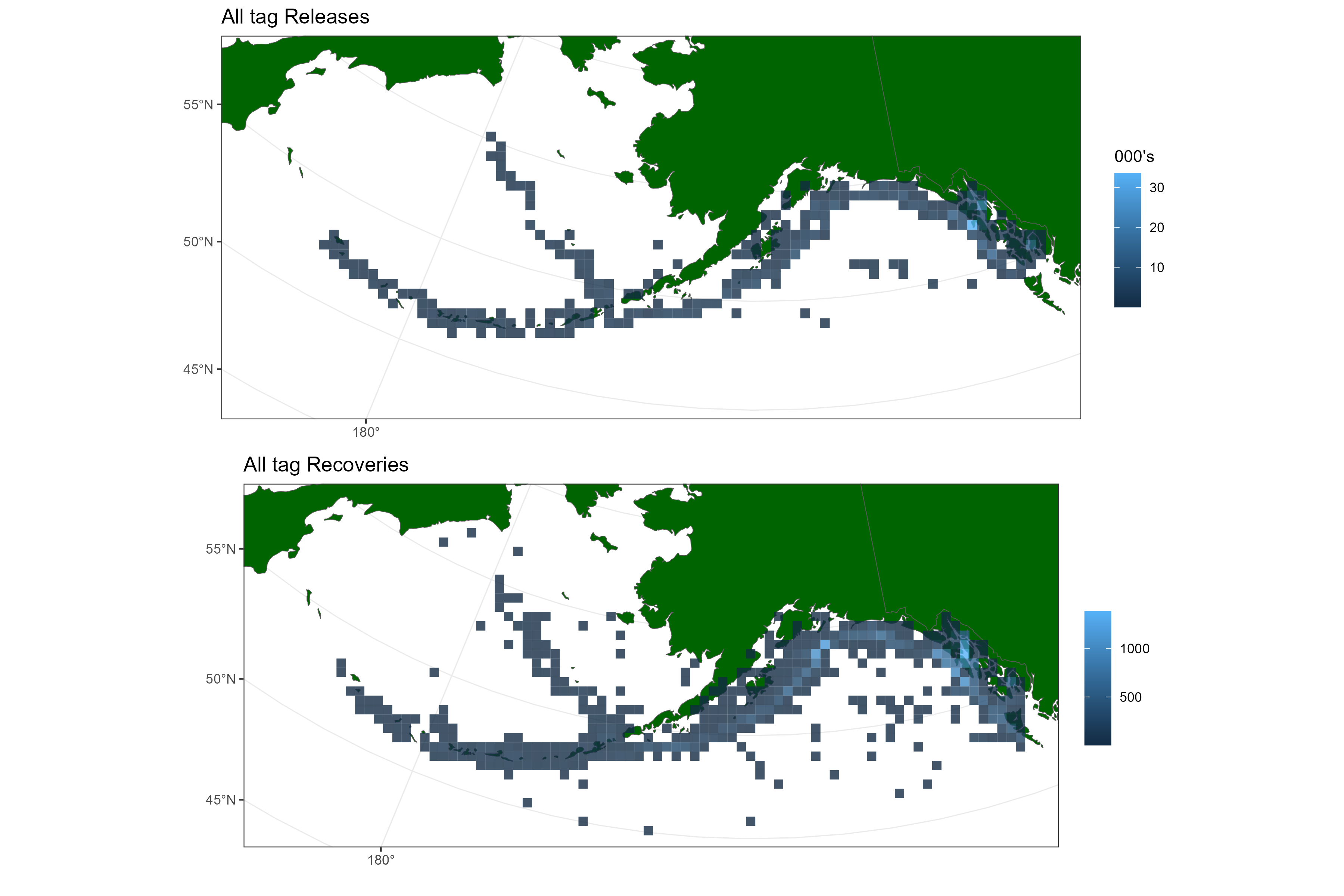

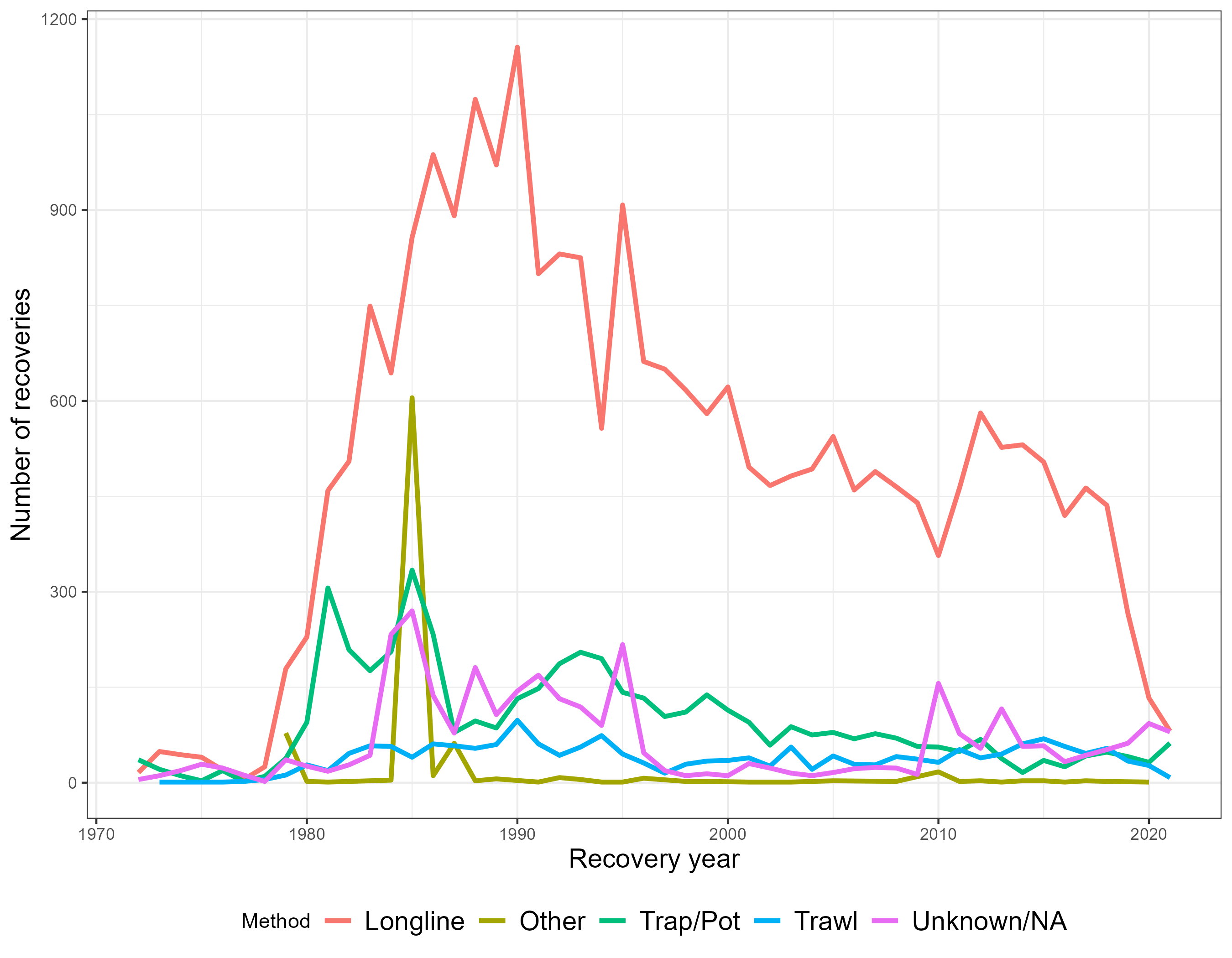

Figure 7.1 shows the spatial distribution of both releases and recaptures, which both have fairly broad spatial distributions which is a good attribute. Figure 7.2 shows the number of recoveries by gear method and year, this highlights a major drop off in recoveries from the Longline gear with no other gear has picked up in. This will have to be discussed with the wider team. In particular, what years to consider this data to be informative.

Figure 7.1: Tag releases and recoveries pooled over all years

Figure 7.2: Recovered fish by gear type and year

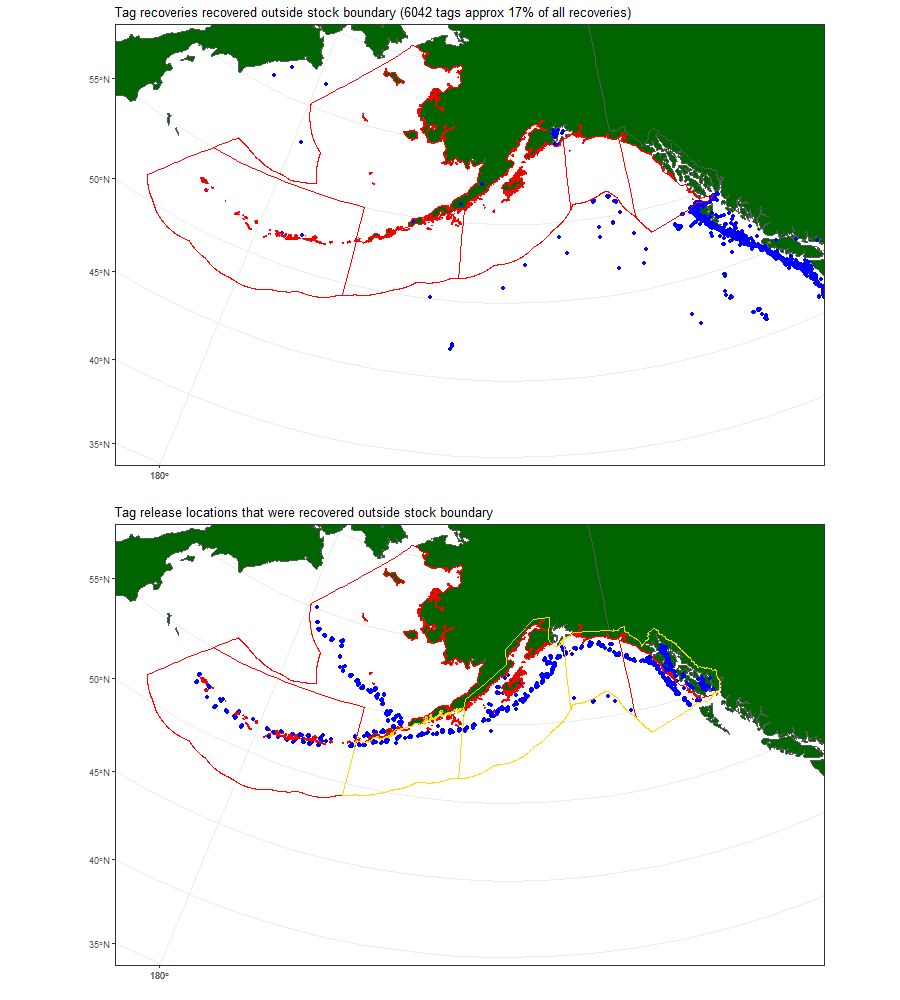

One thing of note is the number of tag-recaptures outside of the stock boundaries, shown in Figure 7.3.

Figure 7.3: Tag recoveries outside of stock boundaries, with release locations (bottom panel).

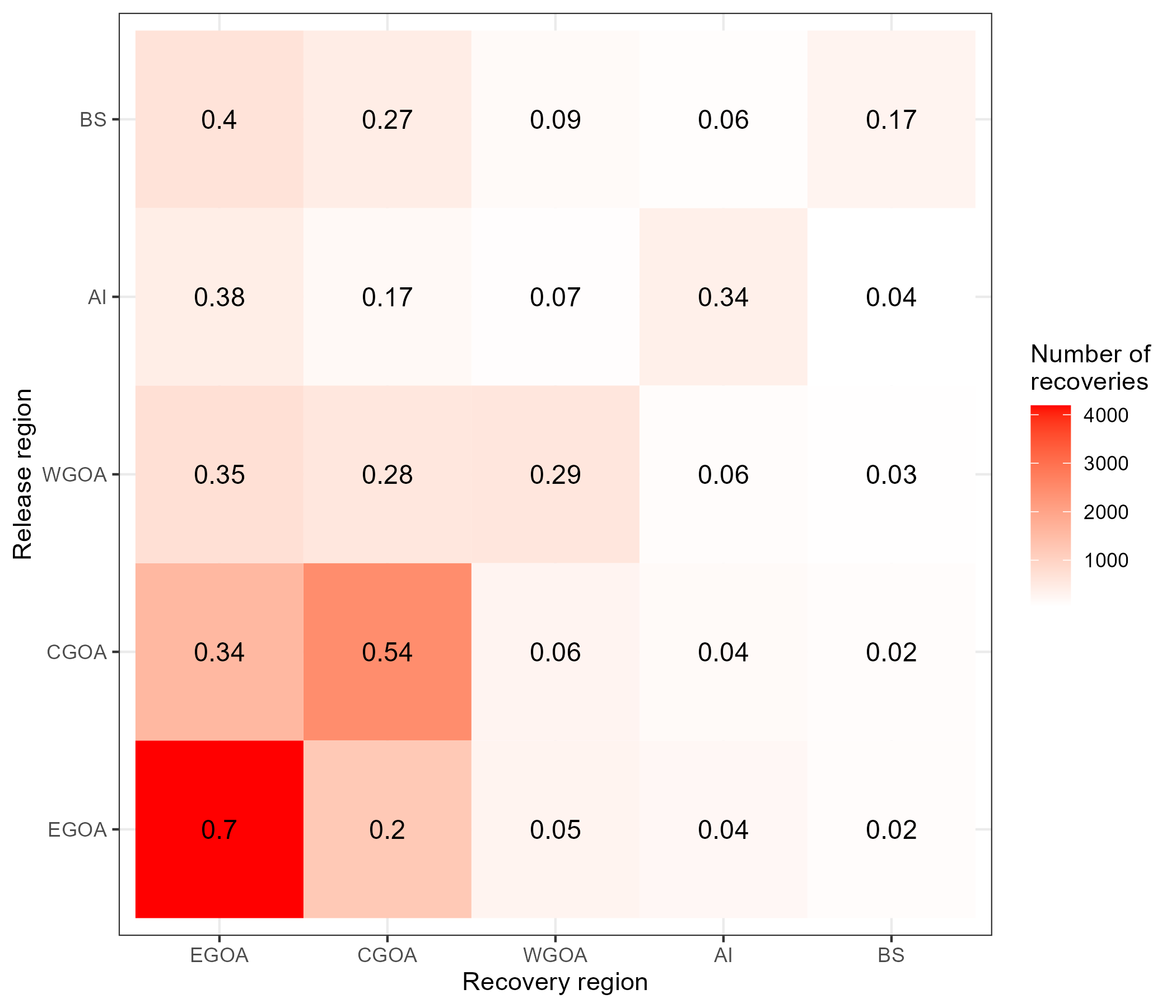

We can crudely look at the proportion of recoveries across recovery regions that were released in a given region, which is shown in Figure 7.4. Care must be taken when interpreting these numbers because recovery rates among regions will differ which this plot is ignoring such as time-at-liberty, spatially varyin reporting rates due to different fishing mortality.

Figure 7.4: Tag recoveries by release and recovery region pooled over all years. Colors are number of tags recovered and text indicates the proportion.

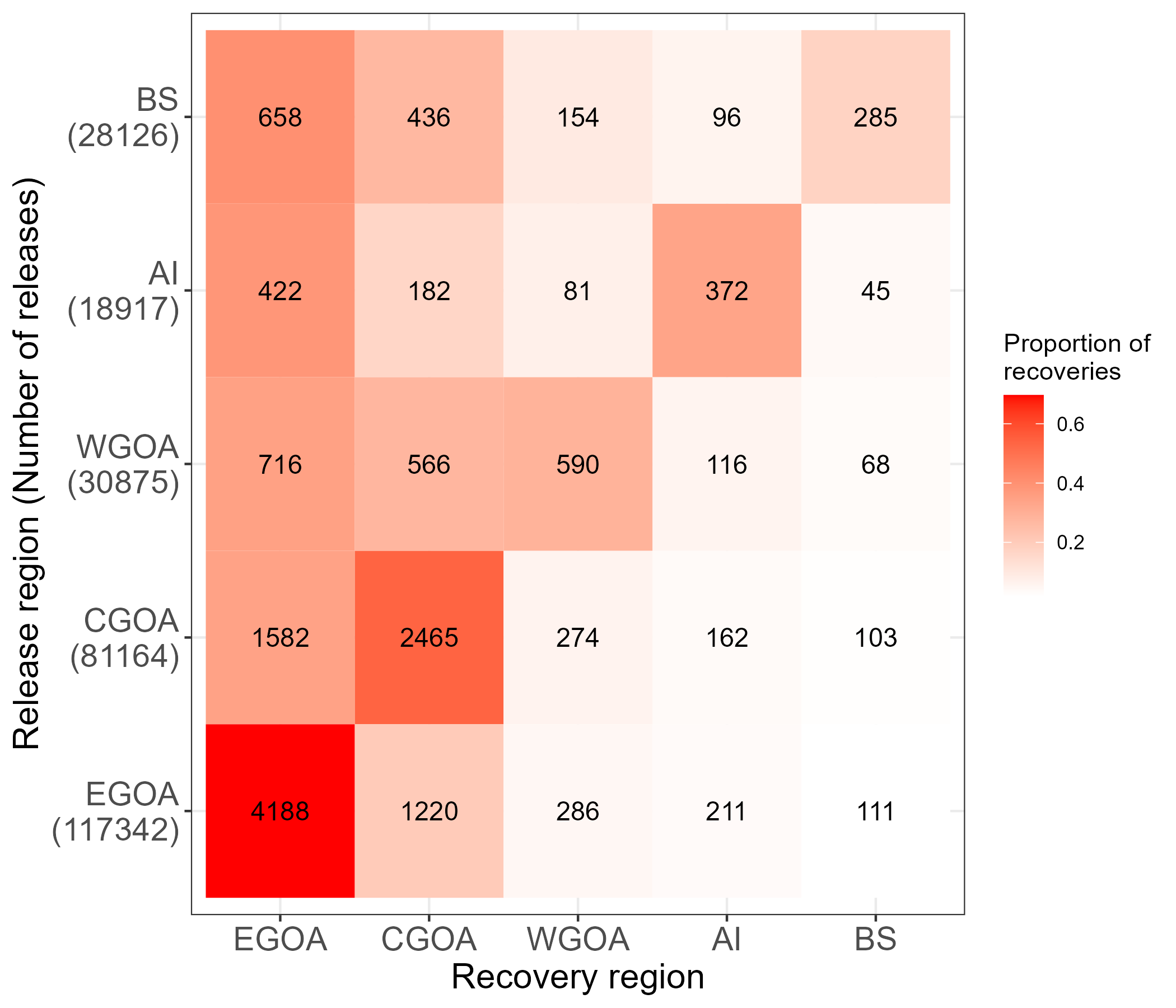

Figure 7.5: Tag recoveries by release and recovery region pooled over all years. Colors proportion of recoveries and text is the number of recoveries among recovery regions.

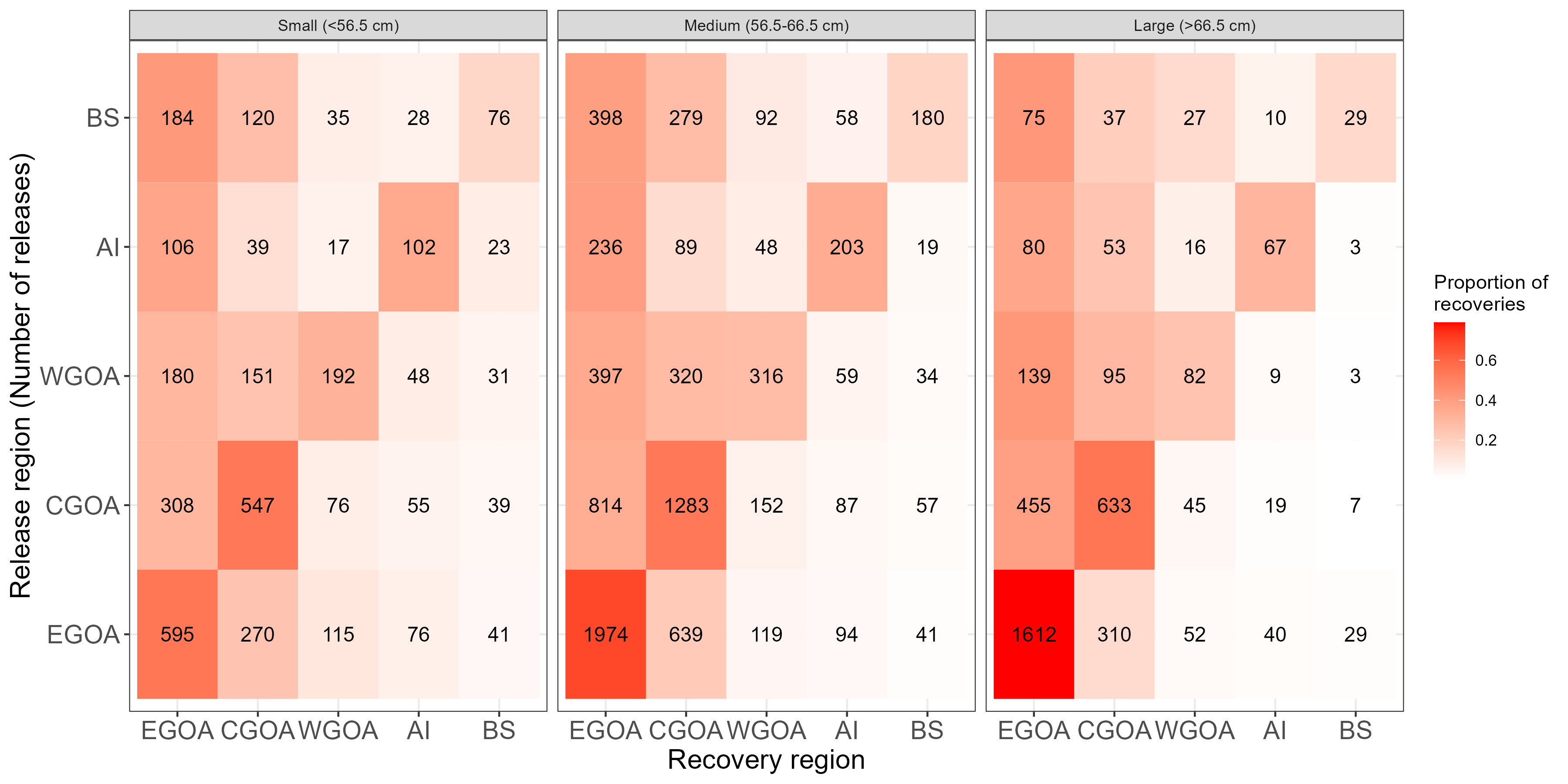

Figure 7.6: Tag recoveries by release and recovery region pooled over all years for different length groups. Colors are number of tags recovered and text indicates the proportion.

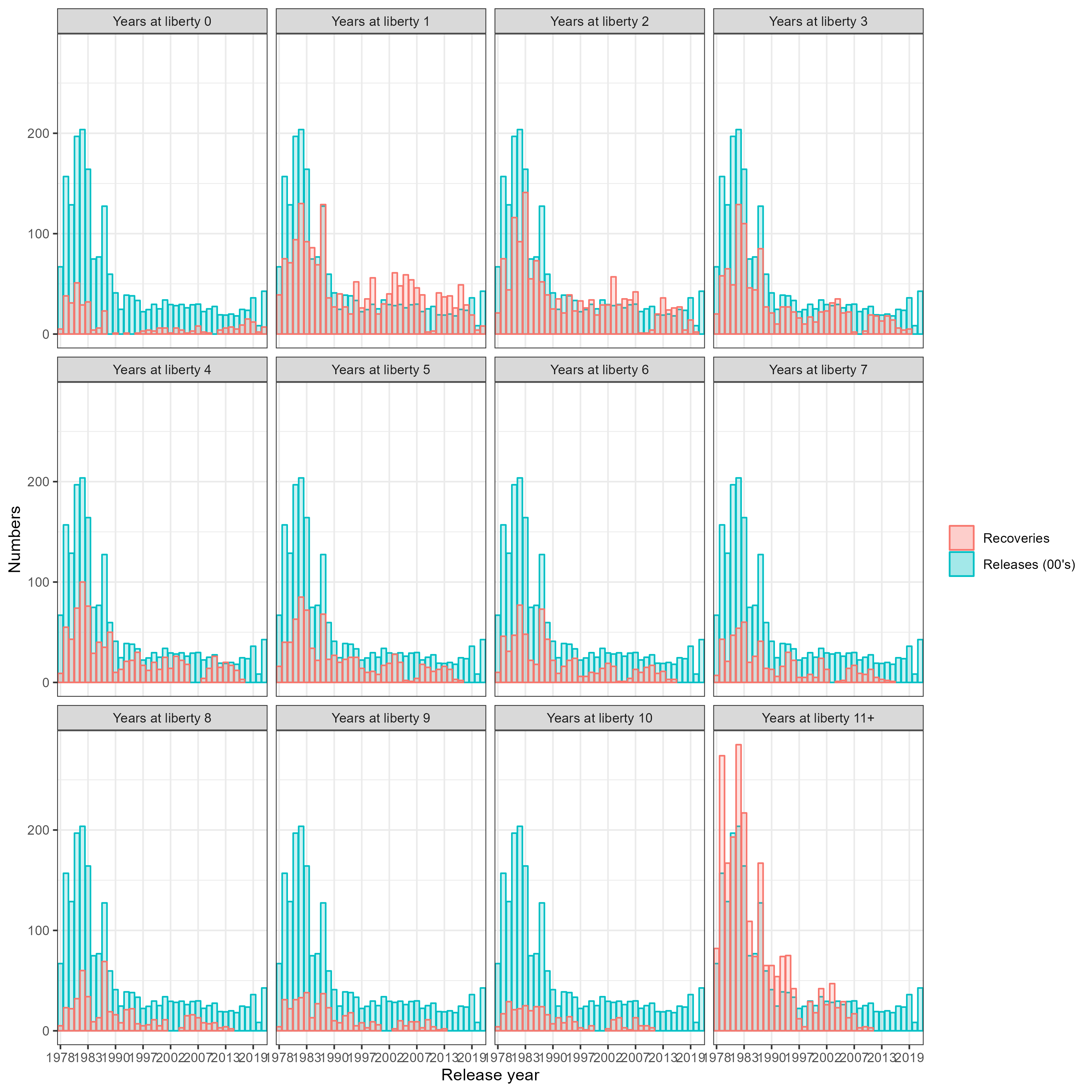

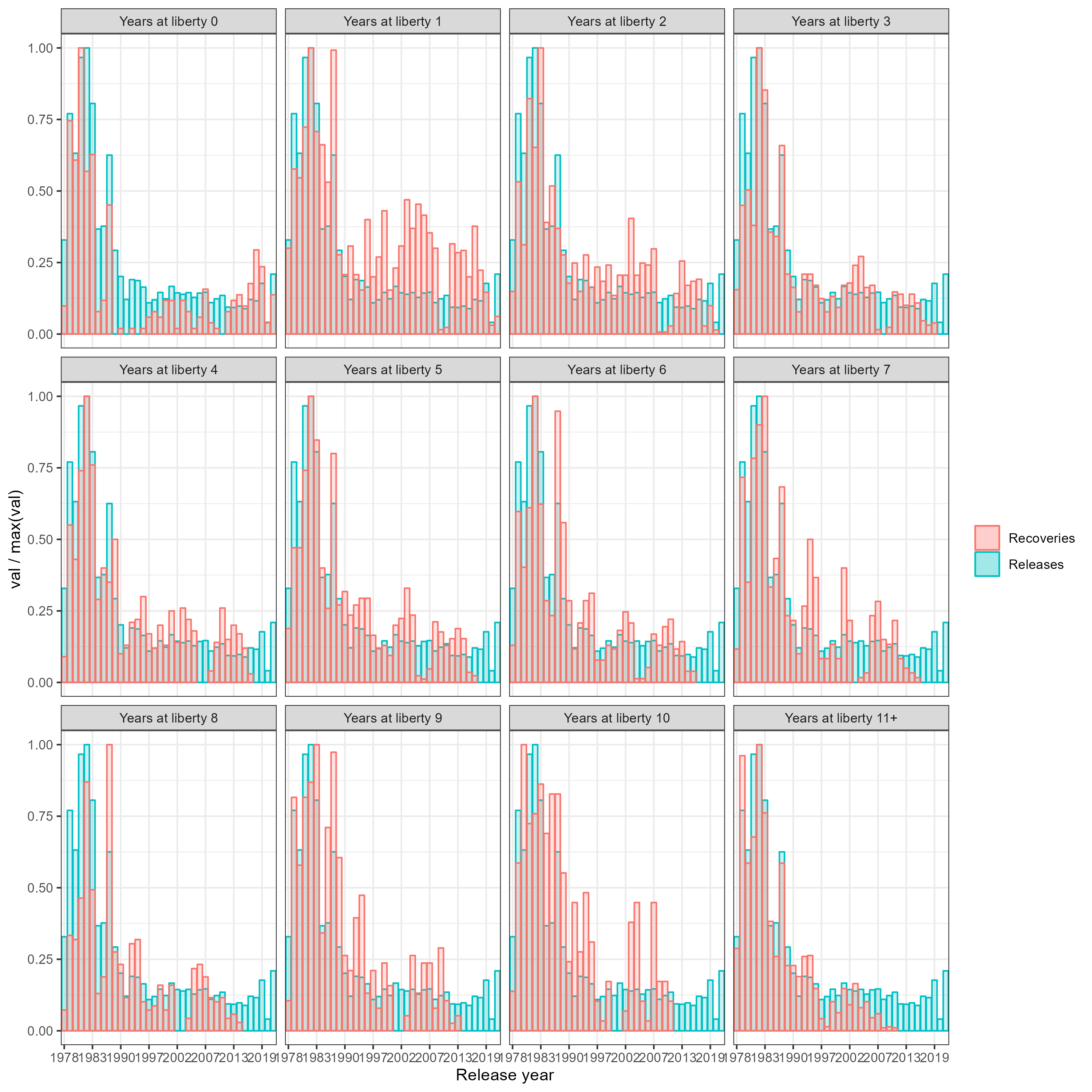

Figure 7.7: Number of tag recoveries and releases by release year and years at liberty

Figure 7.8: Relative (val/max(val)) tag recoveries and releases by release year and years at liberty

Single area recovery model

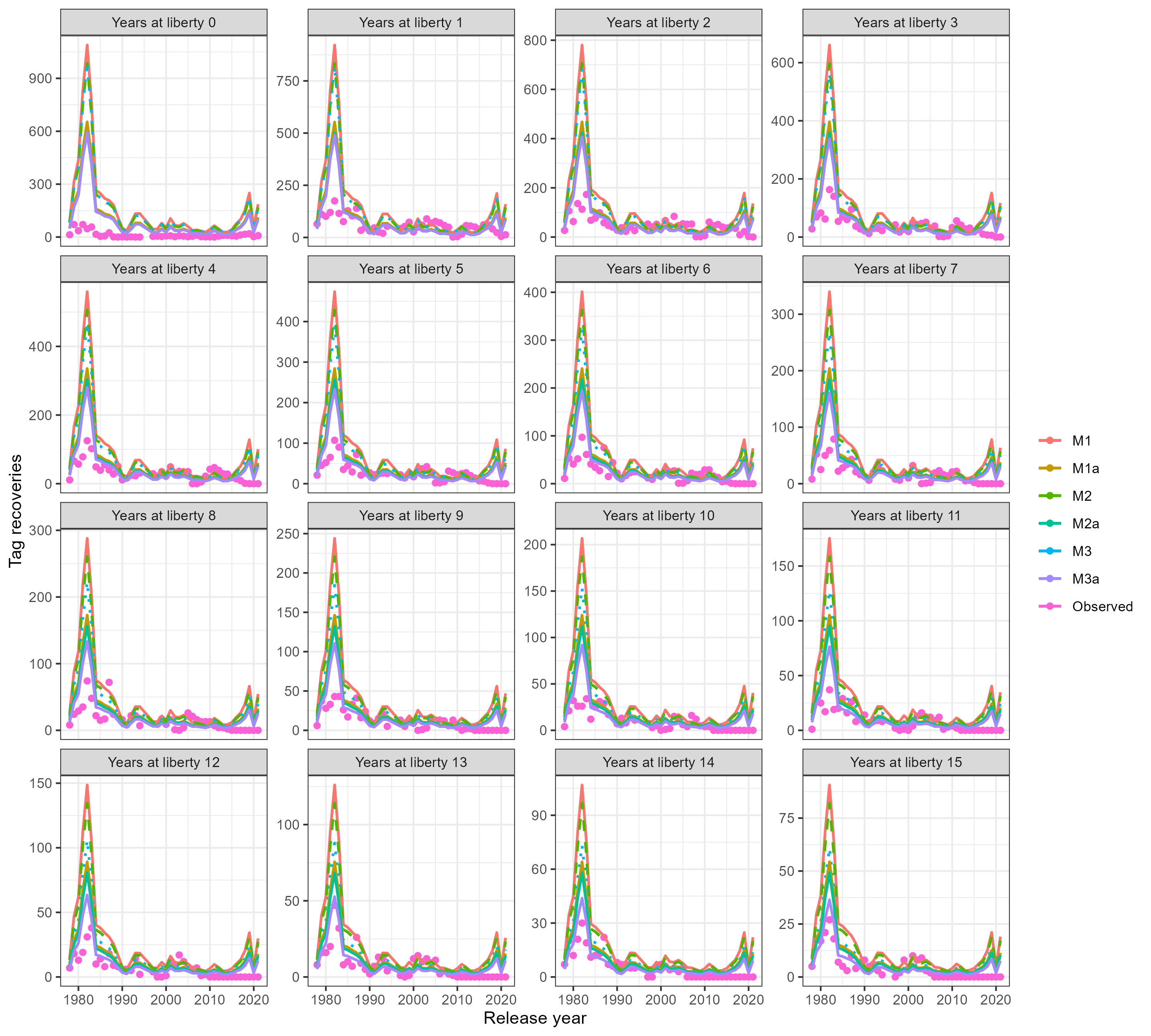

To get an idea regarding tag-mixing and expected recoveries we developed a simple recovery model that was loosely based on Fs and Ms assumed in the sablefish assessment. When we initially run the spatial model with the tagging data there was a scaling problem where the model wanted large annual fishing mortality rates. To explore this we focused on the single area model and looked at expected recoveries based on a range of tag-loss, annual tag-shedding and mortality assumptions

Three tag recovery models were explored

- \(\mathcal{M}_1\)

\[ \widehat{N}^{k}_y = \sum_a T^k_a \left(\exp{-Z_{a}}\right)^y \frac{F_{a}}{Z_{a}} (1 - e^{-Z_{a}})\]

- \(\mathcal{M}_2\)

\[ \widehat{N}^{k}_y = \sum_a T^k_a exp(-M_{tag}) \left(\exp{-Z_{a}}\right)^y \frac{F_{a}}{Z_{a}} (1 - e^{-Z_{a}})\]

- \(\mathcal{M}_2\)

\[ \widehat{N}^{k}_y = \sum_a T^k_a exp(-M_{tag}) \left( \exp{-(\tau + Z_{a})}\right)^y \frac{F_{a}}{Z_{a}} (1 - e^{-Z_{a}})\]

where, \(T^k_a\) numbers of tag releases, released in year \(k\) of age \(a\), \(y\) denotes years at liberty, \(F_{a} = 0.078 * S_a\), where \(S_a\) is logisitc selectivity with \(a_{50} = 5\) and \(ato_{95} = 2\) (the value 0.078 was the mean fishing mortality from the 2021 assessment), \(Z_a = F_a + 0.1\), \(M_{tag}\) is the initial tag induced mortality (=0.1), and \(\tau\) is the annual tag-shedding rate (=0.02). This ignores sex and assumes constant F over years, which is obviously incorrect. However, the purpose was to help identify release years that may be problematic due to mixing or perhaps higher tag induced mortality than initially assumed.

Figure 7.9: Observed and predicted recoveries from a simple model exploration. The a subscript in the model labels assumes tag-reporting of 60%, the absence of the subscript assume 100% tag reporting.

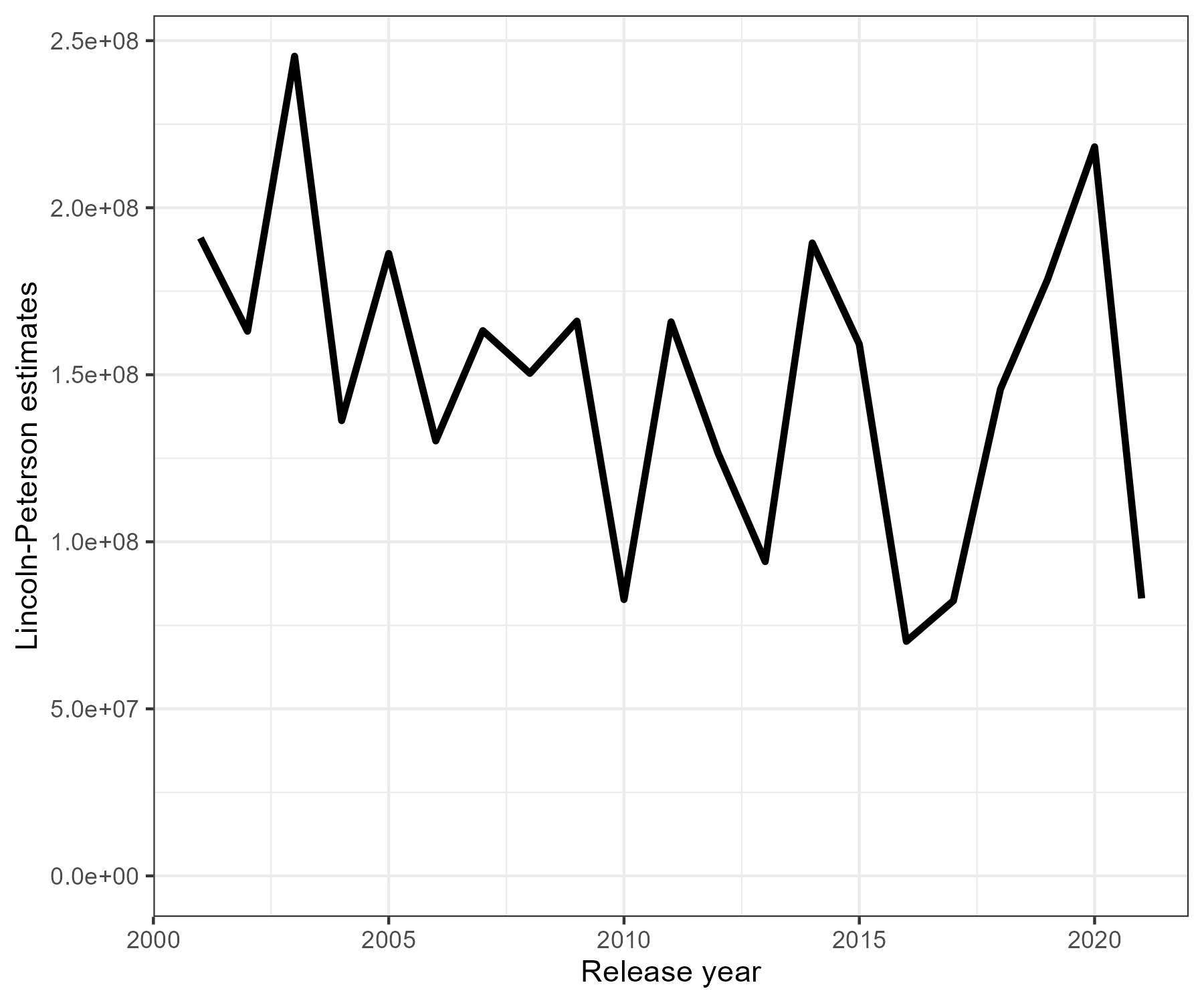

Lincoln-Peterson estimator

We applied a simple Lincoln-Peterson estimators to view changes in abundance over the area of interest using a subset of the tag recoveries. The Lincoln-Peterson estimator follows

\[ \widehat{N} = \frac{n e^{-(\kappa + M)}K\tau}{k} \ . \]

| Symbol | Description |

|---|---|

| \(N\) | Number of fish in the population |

| \(n\) | Number of fish released with a tag |

| \(K\) | Number of fish scanned for tags (fishery catch over the period of recoveries |

| \(k\) | Number of tagged fish recovered |

| \(\tau\) | Reporting/detection rate = 0.276 from Heifetz and Maloney (2001) |

| \(\kappa\) | Annual tag loss or mortality = 0.1 Beamish and McFarlane (1988) |

| \(M\) | Natural mortality = 0.1 based on D. Goethel et al. (2021) |

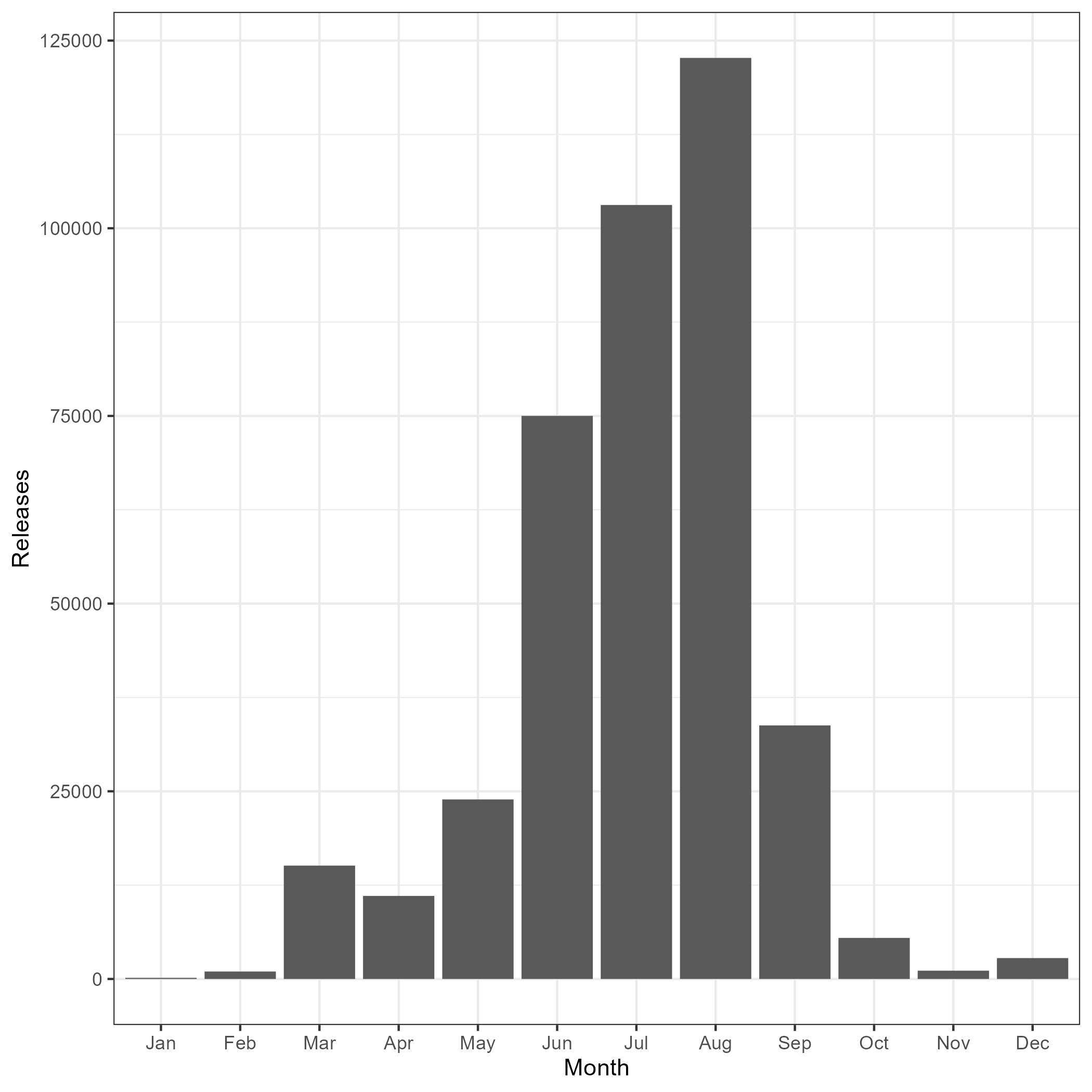

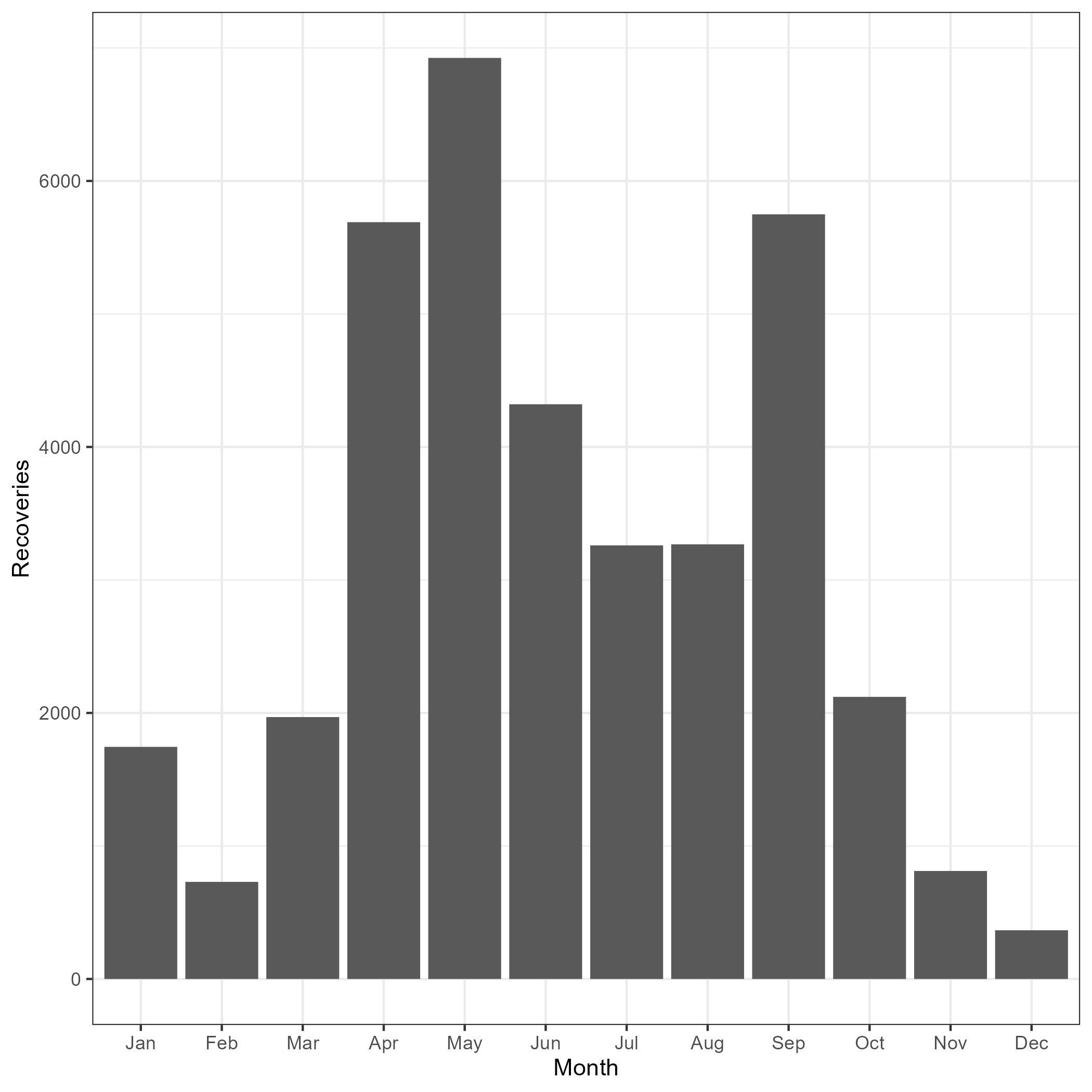

Most of the tags are released during the summer survey (Figure 7.10) but recoveries are more spread out within a year.

Figure 7.10: Tag recovery and release distributions by month

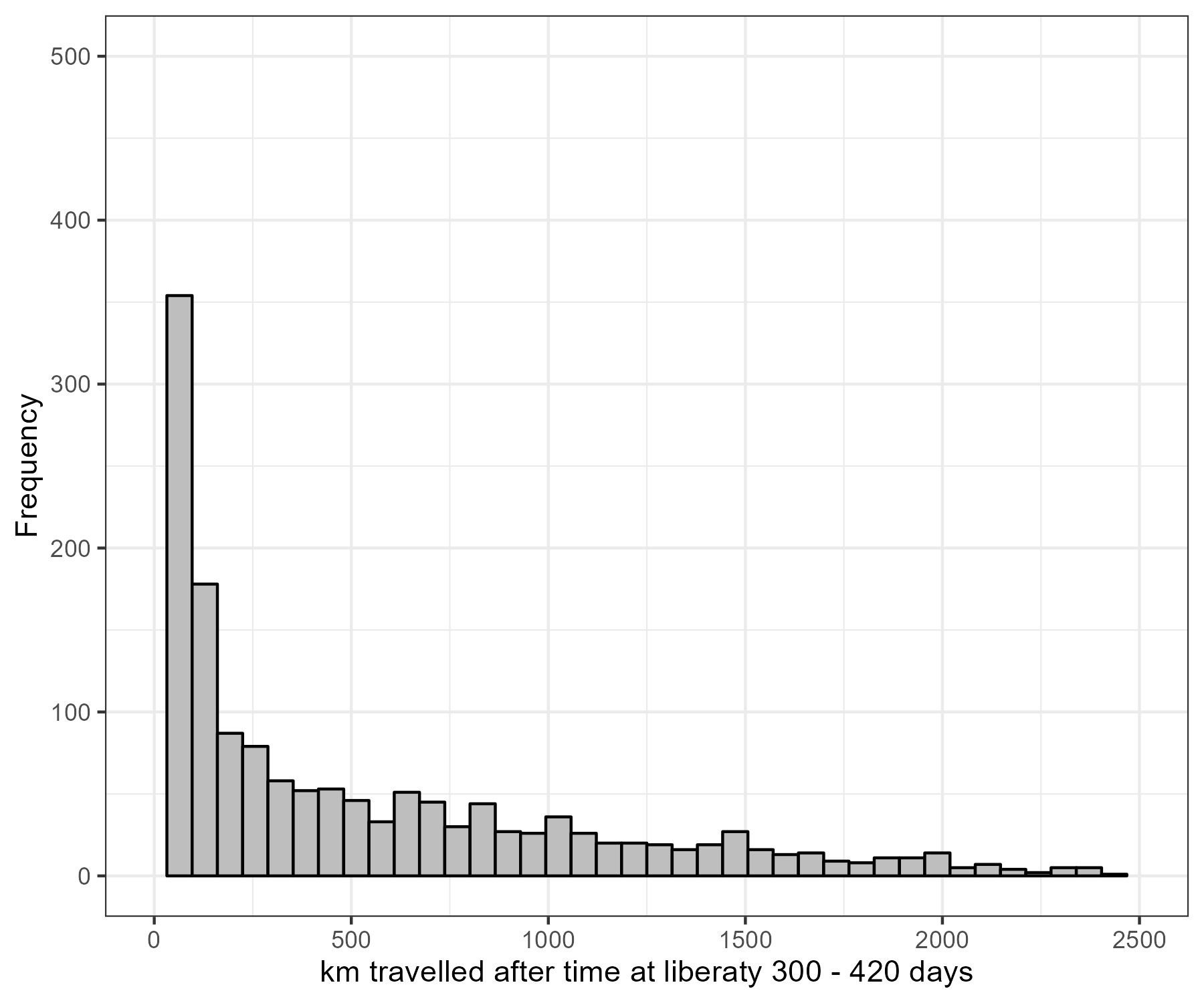

A Lincoln-Peterson estimator based on long line tag recoveries that were at liberty for a year (300 - 420 days) was explored. This time-at-liberty period was chosen so we could calculate annual estimates of abundance and thus derive annual estimates of exploitation rates to compare with the assessment. Due to the large distance traveled by sablefish over this time-period (Figure 7.11), the spatial extent considered was the entire stock region.

Figure 7.11: Distance (km) between release location and recovery location for fish at liberty for a year.

A few calculations/approximations are included in the Lincoln-Peterson estimator, these include tag loss and natural mortality for tagged fish after a year at liberaty, reporting rates from the commercial fishery, and changing reported weights to numbers. The period for calculating catch that was scanned during tag recoveries was the 15 of May to 15 of September. This was chosen as it brackets the monthly peak of releases (Figure 7.10). The other adjustment was converting reported weight into numbers. For this I calculated the mean numbers of fish per tonne based on the observer data. I then used this multiplier for the catch reported in tonnes during the period of recoveries to extract the numbers scanned by the fishery each year.

Figure 7.12: Recovered fish by gear type and year

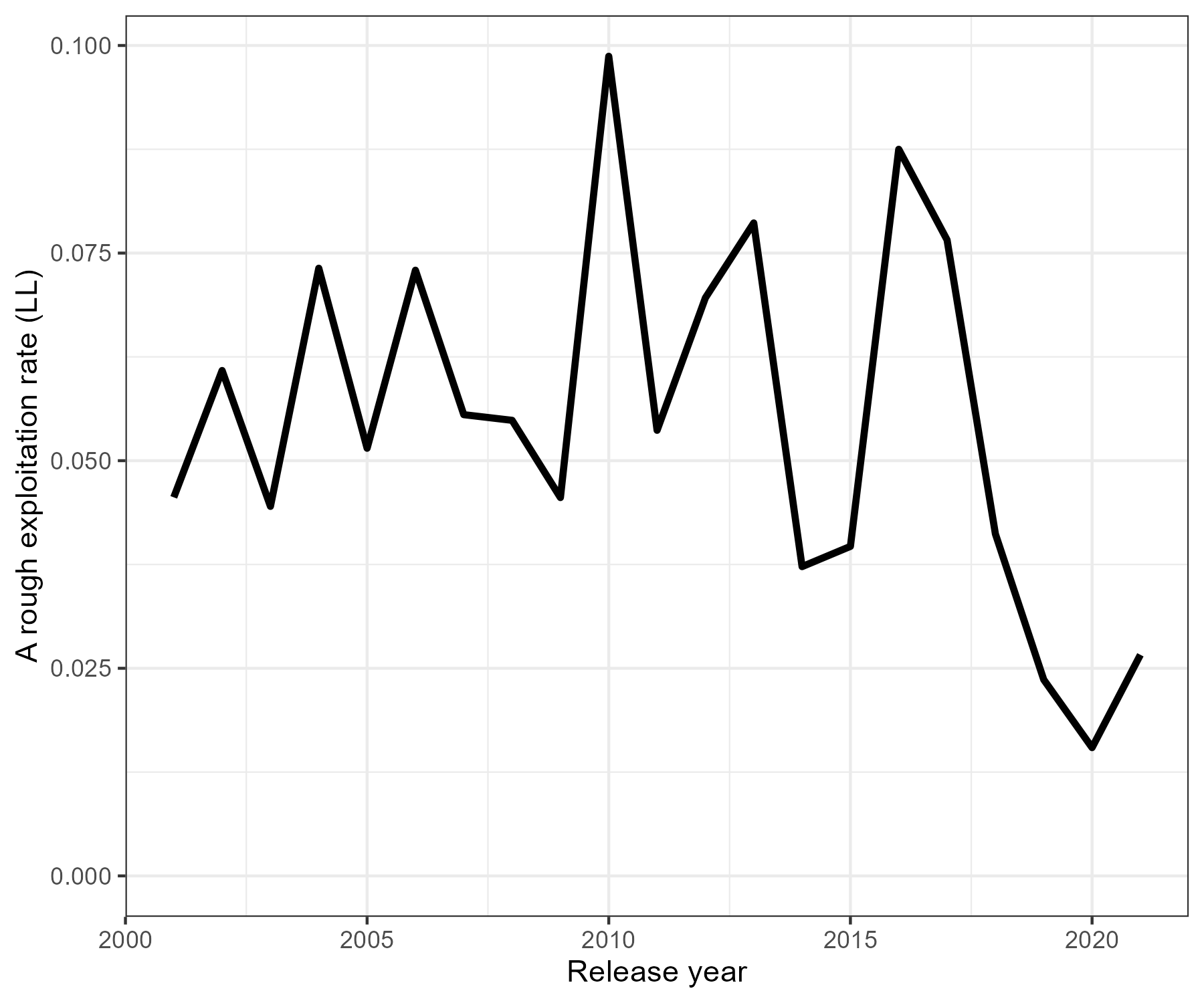

Once we have annual population abundance estimates we can derive a rough annual exploitation rate (\(U_y\)) denoted by

\[ U_y = \frac{C_y}{\widehat{N}} \] where, \(C_y\) is the annual catch in numbers for the Longline fishery shown in Figure 7.13.

Figure 7.13: Exploitation rate for the Longline fishery based on Lincoln-Peterson estimates

Integrating tagging observations in spatial age-structured models

This project intends to explore a range of methods for utilizing tag-recovery observations in spatially disaggregated age-structured stock assessments.

Tagging things to consider with relevant references

- Years to retain tagged fish in the partition “After approximately 9 yr the number of recaptures was small and contributed more to the variance associated with the trends in movement than an improved understanding of these trends” Beamish and McFarlane (1988)

- Reporting rates (Heifetz and Maloney 2001)

- Scan detection rates. Is this not a factor of reporting rates?

- Mixing time and how to deal with it?

- Tag loss “tag loss in the fist year was approximately 10% and after that approximately 2% per year.” Beamish and McFarlane (1988)

- Release conditioning vs recapture conditioning (Vincent, Brenden, and Bence 2020; McGarvey and Feenstra 2002)

- likelihood choice? (Hanselman et al. 2015)